“There’s no frogs in this stew,” says Lavern Meggett, laughing. A daughter of the Gullah Geechee matriarch and best-selling author Emily Meggett, Lavern and her siblings now continue their mother’s culinary legacy, often while hosting events on the remote island where they grew up, off the coast of Charleston, South Carolina.

“Here’s what my mom would say: Everybody would come over after a long week of work, and sit down to a meal. It’s more like a Saturday thing for us, not a Sunday dinner. We lived right by the creek, where we could fish for the shrimp and crabs. The family grew potatoes and corn, too. And when everybody showed up, she boiled up a big pot of Frogmore stew. It brought the family together, sitting around that pot and eating together.”

According to the food historian Joseph E. Dabney, author of The Food, Folklore and Art of Lowcountry Cooking, the origin story of this one-pot meal is centered on a fishing community known as Frogmore, on St. Helena Island in Port Royal Sound. The way he tells it, a shrimper named Richard Gay, whose family owns the Gay Fish Company, reportedly served dinner for his National Guard unit at the Beaufort Armory sometime in the 1960s, dumping chow hall leftovers in a giant stockpot, and then adding fresh-caught shrimp for good measure during the last few minutes of the boil. (Members of Gay’s family still sell wild-caught local shrimp and crabs at their market on St. Helena.)

However, this communal boiled dinner really has deeper roots in North America—indigenous tribes along the Atlantic seaboard prepared seafood and corn with other vegetables in pots over open fires long before Europeans arrived. Then the Gullah Geechee people, descendants of enslaved Africans, brought their love of seasoning to the dish, with the addition of cayenne and smoked sausages. (The Meggetts swear by Roger Wood links.)

Everyone has a different name for it, but the Frogmore stew served at the Meggett’s house on Edisto Island remains true to the one Miss Emily cooked for her weekend guests. “People call it Lowcountry boil or Beaufort stew, or a crab boil, crab crack, and add whatever they want,” says Marvette, another Meggett daughter. “You can find different things to toss in, but it’s not a Frogmore stew.”

Her sister Lavern agrees. “Some family members will add things like broccoli, neck bones, eggs. But mom made it the original way, she didn’t jazz it up.”

The classic recipe for Frogmore stew is easy enough to remember: potatoes, corn, sausage, and shrimp, cooked with seasoning in boiling water. But there are plenty of optional additions.

“In the past this was a ‘clean out your refrigerator’ meal,” says Hope Barber, of Bowens Island Restaurant near Folly Beach. “I’ve seen people even put boiled peanuts in there. One time we added littleneck clams. But our version is basic. We shuck all our own corn, and add an onion and a lemon to the boil.” The restaurant also sources their shrimp and seasoning mix locally.

The Meggetts recall their mother catching blue crabs with a chicken neck tied to a string, and throwing a cast net for the tiny white shrimp that swim in the tidal waterways that define the Carolina Lowcountry’s ACE Basin. Novices who want to learn how to crab the old-school way can join Tia Clark, an environmental activist and coastal protector, during her Casual Crabbing expeditions. Or, if you’d rather let other people do the heavy lifting, restaurants and fish markets from Myrtle Beach on down to Beaufort offer their versions of Frogmore stew.

On Pawleys Island, Harrelson’s Seafood has a ready-to-go, boil-in-a-bag dinner. In Charleston, CudaCo Seafood House sells briny brown shrimp off the boats based in the fishing village of McClellanville, suited to stand out in one-pot dishes like jambalaya, gumbo, and Frogmore stew. During the late season, they sometimes display delicate pink shrimp, which are a rare treat, but all Carolina shrimp taste sweeter than their Gulf cousins, because they feed off spartina grass in cooler waters. Bowens Island Restaurant offers diners their stew with a view of the docks. (But it doesn’t include crab.)

While Miss Emily used to break down her live blue crabs by pouring hot water over their backs when cleaning them, her daughters suggest just throwing them whole in the pot without this step, to avoid being pinched. What’s really important to know about this feed-a-crowd dish is how to serve it. “Just take the pot, drain it, and dump everything on the picnic table, on top of some brown or newspaper,” says Lavern. “Then eat with your hands.”

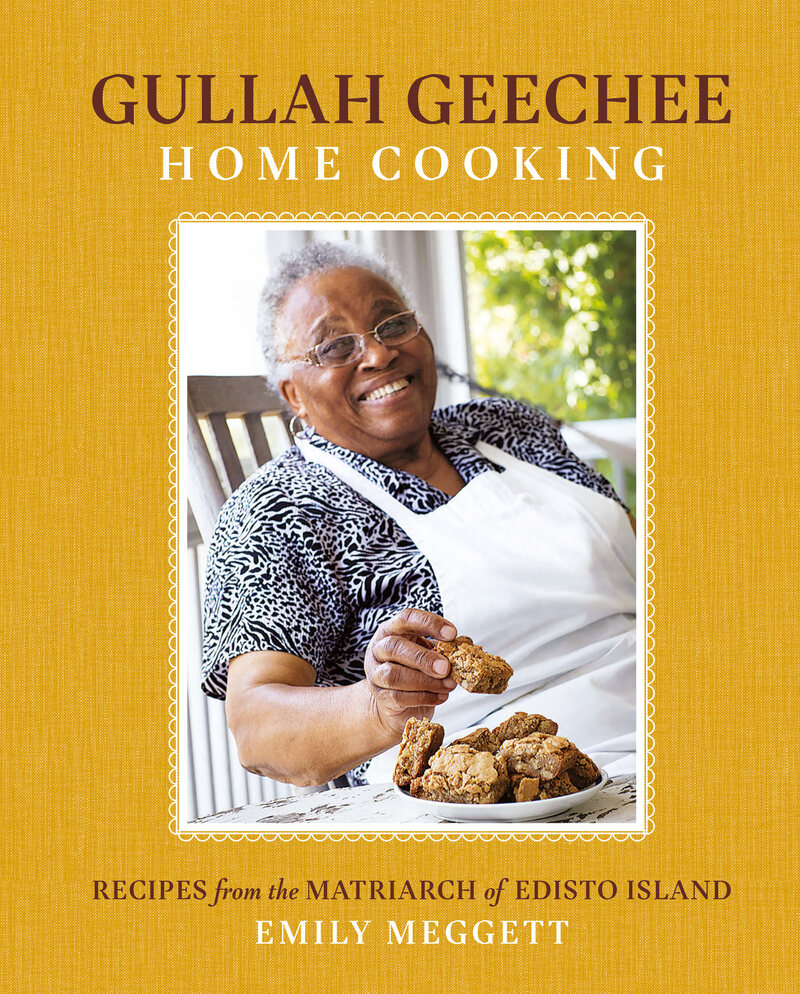

The below recipe is adapted from Emily Meggett’s cookbook, ‘Gullah Geechee Home Cooking.’ For another classic take on Frogmore stew, check out Discover South Carolina’s Frogmore stew recipe.